Introduction

Welcome to this comprehensive guide on Backend Engineering Fundamentals. This article consolidates all the learning materials from Hussein Nasser’s “Fundamentals of Backend Engineering” course into a single, cohesive reference document.

Over the course of this journey, I’ve taken detailed notes on 40+ lectures covering everything from low-level networking protocols to high-level system design patterns. Rather than having these insights scattered across dozens of individual posts, I wanted to create a unified resource that presents the material in a logical learning progression.

What You’ll Find Here:

This guide covers the complete spectrum of backend engineering, organized into eight major parts:

- Foundation - Communication patterns and core protocols

- Application Layer Protocols - The evolution of HTTP and modern web protocols

- Real-Time Communication - WebSockets, gRPC, WebRTC, and Server-Sent Events

- Backend Execution & Concurrency - Processes, threads, and execution patterns

- Connection Management - Socket programming and TCP connection handling

- Load Balancing & Proxying - Distributing traffic and managing connections

- Performance & Optimization - Techniques for building fast, efficient systems

- Backend Patterns & Best Practices - Authentication, idempotency, and design principles

How to Use This Guide:

This article is designed to be both a learning resource and a reference guide. If you’re new to backend engineering, I recommend reading it sequentially, as later sections build on concepts introduced earlier. If you’re looking for specific information, use the table of contents below to jump directly to the topic you need.

Throughout the article, you’ll find cross-references linking related concepts. These connections are important—backend engineering is deeply interconnected, and understanding how different pieces fit together is crucial for building robust systems.

Prerequisites:

This guide assumes basic programming knowledge and familiarity with web concepts. You don’t need to be an expert, but understanding what a client-server architecture is and having written some code will help you get the most out of this material.

Let’s dive in.

Table of Contents

Part I: Foundation - Communication Patterns & Protocols

Part II: Application Layer Protocols

Part III: Real-Time Communication

Part IV: Backend Execution & Concurrency

Part V: Connection Management & Socket Programming

Part VI: Load Balancing & Proxying

Part VII: Performance & Optimization

Part VIII: Backend Patterns & Best Practices

- Request Journey and System Design

- Authentication and Authorization

- Idempotency and Reliability

- Software Design Principles

- Server-Sent Events and Streaming Architectures

Conclusion

Final Thoughts and Key Takeaways

Part I: Foundation - Communication Patterns & Protocols

1. Backend Communication Fundamentals

Before diving into specific protocols and technologies, let’s establish the foundational patterns that govern how backend systems communicate. At its core, backend communication is about moving data between systems reliably and efficiently.

The Four Core Communication Patterns:

Every backend system uses one or more of these fundamental patterns:

-

Request-Response: The client sends a request, the server processes it, and returns a response. This is the most common pattern, used in HTTP, DNS, SSH, and database protocols.

-

Push-Pull: The server pushes updates to clients, or clients pull data as needed. This pattern is common in message queues and data synchronization systems.

-

Long Polling: The client repeatedly requests updates at intervals, keeping a connection open until new data is available.

-

Publish-Subscribe: Clients subscribe to topics and receive notifications when new data is published. This pattern decouples producers from consumers.

Understanding these patterns is crucial because they influence everything from API design to system architecture. Most modern systems combine multiple patterns—for example, a web application might use request-response for page loads, publish-subscribe for notifications, and long polling for real-time updates.

2. Protocol Properties and the OSI Model

Every communication protocol is designed to solve specific problems, and understanding their properties helps us choose the right tool for the job. A protocol is simply a set of rules that allows two parties to communicate effectively.

Why Protocols Matter:

Protocols aren’t arbitrary—they’re carefully designed with specific trade-offs. TCP, for instance, was created in the 1960s for low-bandwidth networks. Today’s data centers push TCP to its limits, leading to newer protocols like Homa (2022) that optimize for modern hardware. The key insight is that every protocol makes deliberate choices about reliability, performance, and complexity.

Key Protocol Properties:

When evaluating any protocol, consider these characteristics:

-

Data Format: Text-based (JSON, XML, HTTP) vs. binary (Protocol Buffers, gRPC, HTTP/2). Text is human-readable but less efficient; binary is optimized for machines.

-

Transfer Mode: Message-based (HTTP, UDP) with clear boundaries vs. stream-based (TCP) with continuous byte flows. Message-based protocols package data into discrete units, while streams require applications to parse boundaries.

-

Addressing: How the protocol identifies source and destination—DNS for domain names, IP for network routing, MAC addresses for local networks, and ports for application multiplexing.

-

Directionality: Unidirectional (one-way), bidirectional (two-way), full-duplex (simultaneous two-way), or half-duplex (taking turns).

-

State Management: Stateful protocols (TCP, gRPC) maintain session information, while stateless protocols (UDP, HTTP) treat each message independently.

-

Reliability: Protocols like TCP guarantee delivery with retransmissions and flow control, while UDP provides best-effort delivery with no guarantees.

The OSI Model:

The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model divides networking into seven layers, providing a framework for understanding how data moves through a network. While the strict boundaries can blur in practice, the model remains invaluable for troubleshooting and system design.

The seven layers are:

- Physical Layer: Transmission media (electrical signals, light, radio waves)

- Data Link Layer: Frames with MAC addresses; switches operate here

- Network Layer: IP packets and routing; routers work at this layer

- Transport Layer: TCP and UDP; provides end-to-end communication

- Session Layer: Connection establishment and state management

- Presentation Layer: Data serialization and encoding

- Application Layer: End-user protocols (HTTP, FTP, gRPC)

Copyrights © FS

The beauty of this layered approach is abstraction—applications don’t need separate versions for WiFi, Ethernet, or LTE because lower layers handle the conversion. Each layer can be updated independently, making networks more maintainable and extensible.

2.1. Network Layer: IP, TCP, and UDP

At the heart of internet communication are three fundamental protocols: IP (Internet Protocol), TCP (Transmission Control Protocol), and UDP (User Datagram Protocol). Understanding these protocols is essential for any backend engineer.

TCP: The Reliable Workhorse

TCP is the backbone of reliable networking. When I first learned about TCP, I was amazed at how it ensures data arrives perfectly every time—no lost packets, no jumbled order. It’s like the internet’s most reliable delivery service.

TCP is a layer 4 protocol that sits on top of IP. While IP handles routing packets between devices, TCP ensures reliable, ordered delivery. It’s connection-oriented, meaning it establishes a dedicated connection before transmitting data.

Key TCP Characteristics:

-

Reliability: TCP guarantees delivery through acknowledgments and retransmissions. If a segment is lost or corrupted, TCP automatically resends it.

-

Order Guarantee: Packets can take different routes and arrive out of order. TCP uses sequence numbers to reassemble them correctly.

-

Flow Control: TCP prevents overwhelming the receiver using a sliding window mechanism, limiting how much data can be sent before receiving acknowledgments.

-

Congestion Control: TCP adjusts its sending rate based on network conditions, using techniques like Explicit Congestion Notification (ECN) to avoid network congestion.

-

Statefulness: TCP maintains connection state, storing sequence numbers and window sizes in a session identified by a four-tuple (source IP, source port, destination IP, destination port).

-

Connection Management: TCP uses a three-way handshake (SYN, SYN-ACK, ACK) to establish connections and a four-way handshake (FIN, ACK, FIN, ACK) to close them gracefully.

How TCP Connections Work:

The three-way handshake is fundamental to TCP. When a client wants to connect:

- Client sends SYN (synchronize) to the server

- Server responds with SYN-ACK (synchronize-acknowledge)

- Client sends ACK (acknowledge)

This handshake ensures both sides agree on initial sequence numbers and are ready to communicate. Behind the scenes, the OS kernel manages two queues:

- SYN queue: Holds connections that have sent SYN but haven’t completed the handshake

- Accept queue: Holds fully-established connections waiting for the application to accept them

When your application calls listen() on a socket, the kernel handles the entire handshake process. Your code only calls accept() to retrieve a fully-established connection from the accept queue. This separation between kernel space (where TCP lives) and user space (where your application runs) is crucial for performance.

TCP Trade-offs:

While TCP is powerful, it has costs:

-

Latency: The three-way handshake and acknowledgment process introduce delays, problematic for time-sensitive applications like gaming or video streaming.

-

Overhead: TCP headers (20-60 bytes) and control mechanisms add extra data to each packet, inefficient for small transfers.

-

Resource Intensive: Maintaining connection state requires memory and CPU. Even advanced systems like WhatsApp are limited to about 3 million connections per server.

-

Complexity: Features like flow and congestion control make TCP more complex to implement and troubleshoot than simpler protocols.

UDP: Simple and Fast

UDP (User Datagram Protocol) takes the opposite approach from TCP. It’s a simple, message-oriented protocol that prioritizes speed over reliability. UDP is connectionless—no handshake, no state, no guarantees.

Key UDP Characteristics:

-

Message-Based: Each UDP datagram is independent with fixed boundaries. Unlike TCP’s byte stream, UDP preserves message boundaries.

-

Stateless: No connection establishment or state tracking. Each message is fire-and-forget.

-

Minimal Header: Only 8 bytes compared to TCP’s 20-60 bytes, reducing overhead.

-

Multiplexing: Like TCP, UDP uses ports to distinguish between applications on the same host.

-

No Reliability: UDP doesn’t guarantee delivery, order, or error-free transmission. Lost packets stay lost.

-

No Flow or Congestion Control: The sender doesn’t adjust rates based on network conditions—applications must handle this if needed.

When to Use UDP:

UDP shines in scenarios where speed matters more than perfect delivery:

- Video Streaming & Gaming: Occasional packet loss is acceptable; speed is critical

- DNS Queries: Small, fast lookups where retrying is cheaper than TCP overhead

- VPNs: Many VPN implementations use UDP to avoid connection-oriented overhead

- WebRTC: Browser-based peer-to-peer communication uses UDP with application-layer reliability

UDP Trade-offs:

UDP’s simplicity is both its strength and weakness:

- Pros: Low latency, minimal overhead, scales well (no state to maintain), simple to implement

- Cons: No reliability guarantees, vulnerable to packet loss, no congestion control (can flood networks), susceptible to spoofing attacks

Practical Example: TCP vs UDP Servers

Here’s how different these protocols look in practice. A simple TCP server in Node.js:

const net = require("net");

const server = net.createServer((socket) => {

console.log(`TCP connection from ${socket.remoteAddress}:${socket.remotePort}`);

socket.write("Hello from TCP server");

socket.on("data", (data) => {

console.log("Received:", data.toString());

});

});

server.listen(8800, "127.0.0.1");

And a UDP server:

const dgram = require("dgram");

const server = dgram.createSocket("udp4");

server.on("message", (msg, rinfo) => {

console.log(`UDP message from ${rinfo.address}:${rinfo.port}`);

console.log("Message:", msg.toString());

});

server.bind(8801, "127.0.0.1");

The TCP version establishes a connection and maintains state, while the UDP version simply receives messages without any connection concept. Node.js’s event-driven model handles multiple connections automatically, but the underlying protocol differences remain.

The choice depends on your requirements:

- Use TCP when: You need guaranteed delivery, ordered data, or can’t tolerate loss (web browsing, file transfers, databases, email)

- Use UDP when: Speed is critical, occasional loss is acceptable, or you’re implementing custom reliability (streaming, gaming, DNS, VoIP)

Many modern protocols like QUIC (used in HTTP/3) actually build reliability on top of UDP, getting the best of both worlds—UDP’s speed with application-layer reliability mechanisms. We’ll explore this more when we discuss HTTP/3 and QUIC.

Understanding TCP and UDP is fundamental because almost every network application uses one or the other. They represent different philosophies: TCP’s “make sure everything arrives perfectly” versus UDP’s “send it fast and move on.” Both have their place in the backend engineer’s toolkit.

Part II: Application Layer Protocols

3. HTTP Evolution: From 1.1 to 3.0

Now that we understand the transport layer with TCP and UDP, let’s move up the stack to the application layer, where HTTP lives. HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is the foundation of the web, and its evolution tells a fascinating story about how we’ve optimized web performance over the past three decades.

The journey from HTTP/1.1 to HTTP/3 represents a continuous effort to make the web faster, more efficient, and more reliable. Each version addresses specific limitations of its predecessor while introducing new capabilities. Understanding this evolution is crucial for backend engineers because the protocol you choose can dramatically impact your application’s performance.

3.1. HTTP/1.1: The Foundation

HTTP/1.1 has been the workhorse of the web since 1997. Despite being over 25 years old, it’s still widely used today, powering countless websites and APIs. Its longevity speaks to both its simplicity and effectiveness.

What Makes HTTP/1.1 Tick:

HTTP/1.1 is a text-based, client-server protocol built on top of TCP. The client (usually a browser) sends a request, and the server responds with the requested resource. It’s stateless—each request is independent, with no memory of previous interactions.

The basic structure is straightforward. A request includes:

- Method: GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, HEAD, etc.

- Path: The resource location (e.g.,

/about) - Headers: Metadata as key-value pairs

- Body: Optional data (empty for GET, populated for POST)

A response includes:

- Status Code: 200 OK, 404 Not Found, 500 Internal Server Error, etc.

- Headers: Response metadata

- Body: The actual content (HTML, JSON, images, etc.)

Here’s what a simple HTTP/1.1 request looks like:

GET /about HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

User-Agent: curl

Accept: */*

And the response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

Content-Length: 1234

<html>...</html>

And the visualization:

Copyrights © oreilly

Key Features:

-

Persistent Connections: Unlike HTTP/1.0, which closed connections after each request, HTTP/1.1 introduced the “Keep-Alive” header to reuse TCP connections for multiple requests. This was a huge improvement—establishing TCP connections is expensive (three-way handshake, slow start), so reusing them reduces latency significantly.

-

Mandatory Host Header: This simple addition enabled multi-homed hosting, where multiple domains can share a single IP address. The server uses the Host header to determine which site to serve. This was revolutionary for hosting providers and remains essential today.

-

Pipelining: HTTP/1.1 allows sending multiple requests without waiting for responses. However, this feature is disabled by default in most browsers due to head-of-line blocking—if one response is slow, all subsequent responses are delayed. Only Opera fully supported it, and even then, issues with proxies and servers made it unreliable.

The Limitations:

While HTTP/1.1 served the web well, it has significant drawbacks:

-

No Multiplexing: Each request ties up a connection until the response arrives. Browsers work around this by opening multiple connections (typically 6 per domain), but this is inefficient and resource-intensive.

-

No Compression: Headers are sent as plain text with every request, creating overhead, especially for requests with many headers or cookies.

-

No Streaming: HTTP/1.1 requires the entire response to be ready before sending, with

Content-Lengthspecifying the size upfront. This prevents true streaming or server-sent events. -

Security Vulnerabilities: HTTP smuggling attacks exploit inconsistencies in how servers handle

Content-LengthandTransfer-Encodingheaders. An attacker can craft requests that are interpreted differently by front-end and back-end servers, potentially bypassing security controls.

When to Use HTTP/1.1:

Despite its age, HTTP/1.1 remains relevant for:

- Simple applications with few concurrent requests

- Legacy systems that don’t support newer protocols

- Debugging and development (its text-based format is human-readable)

- APIs where simplicity matters more than performance

3.2. HTTP/2: Multiplexing and Performance

HTTP/2, standardized in 2015, was designed to address HTTP/1.1’s performance bottlenecks while maintaining backward compatibility. The key insight was that the web had changed—modern websites load dozens or hundreds of resources (images, scripts, stylesheets), and HTTP/1.1’s one-request-per-connection model couldn’t keep up.

The Game-Changer: Multiplexing

HTTP/2’s headline feature is multiplexing—the ability to send multiple requests and responses simultaneously over a single TCP connection. Instead of opening 6 connections and queuing requests, HTTP/2 uses one connection with multiple independent streams.

Each stream has a unique ID (odd numbers for client requests, even for server responses), allowing the server to process requests concurrently and send responses as they’re ready, regardless of order. This eliminates the connection limit bottleneck and dramatically improves performance for resource-heavy pages.

Key Features:

-

Binary Protocol: Unlike HTTP/1.1’s text format, HTTP/2 uses binary framing. This is more efficient for machines to parse but less human-readable. Each frame includes metadata like stream ID, frame type, and flags.

-

Header Compression: HTTP/2 uses HPACK compression to reduce header overhead. Since many headers repeat across requests (like cookies and user agents), compression can save significant bandwidth.

-

Stream Prioritization: Clients can assign priorities to streams, helping servers decide which resources to send first. For example, CSS might be prioritized over images to render the page faster.

-

Server Push (Deprecated): HTTP/2 initially allowed servers to proactively push resources to clients. However, this was abandoned because servers often pushed resources the client already had cached, wasting bandwidth. It’s been replaced by “early hints” (HTTP 103 status code) that suggest resources without sending them.

Performance Comparison:

The lecture included a practical test loading 100 images on a webpage, comparing HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2 on a simulated 3G connection:

- HTTP/1.1: Limited to 6 concurrent connections, images loaded in batches with noticeable delays between batches.

- HTTP/2: All images loaded concurrently over a single connection, completing “way faster” with no artificial connection limits.

Copyrights © wallarm

This test highlights HTTP/2’s strength for modern web applications with many resources.

The Trade-offs:

HTTP/2 isn’t perfect:

-

TCP Head-of-Line Blocking: While HTTP/2 eliminates application-level head-of-line blocking, it still suffers from TCP’s version. If a single packet is lost, TCP’s in-order delivery requirement stalls all streams until the packet is retransmitted. This is especially problematic on lossy networks like mobile connections.

-

Increased Server Complexity: Managing multiple streams, flow control, and prioritization requires more CPU and memory than HTTP/1.1’s simpler model.

-

Not Always Necessary: For applications with few requests or fast responses, HTTP/1.1’s simplicity may be sufficient. HTTP/2’s benefits shine with high request volumes.

When to Use HTTP/2:

HTTP/2 is ideal for:

- Modern web applications with many resources

- High-traffic websites where performance matters

- APIs with frequent, concurrent requests

- Any scenario where reducing latency is critical

Most major websites and CDNs now support HTTP/2, and it’s often enabled by default in modern web servers.

3.3. HTTPS and TLS: Securing the Web

Before diving into HTTP/3, we need to understand HTTPS and TLS (Transport Layer Security), which secure HTTP traffic. While not a version of HTTP per se, HTTPS is fundamental to modern web communication—so much so that browsers now warn users about non-HTTPS sites.

What is HTTPS?

HTTPS is simply HTTP running over TLS. TLS provides three critical security features:

- Encryption: Scrambles data so only the intended recipient can read it

- Authentication: Verifies the server’s identity to prevent impersonation

- Integrity: Ensures data hasn’t been tampered with during transmission

How TLS Works:

TLS uses a clever combination of symmetric and asymmetric encryption:

-

Asymmetric Encryption: Uses a public key (anyone can encrypt) and a private key (only the owner can decrypt). This is used during the TLS handshake to securely exchange keys and authenticate the server. Algorithms like RSA and Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) are common, but they’re computationally expensive.

-

Symmetric Encryption: Uses the same key for encryption and decryption. It’s much faster than asymmetric encryption, making it ideal for encrypting large amounts of data. Algorithms like AES and ChaCha20 are widely used.

The TLS handshake combines both: asymmetric encryption securely establishes a shared symmetric key, which is then used for the actual data transfer. This gives you the security of asymmetric encryption with the performance of symmetric encryption.

The TLS Handshake:

When you connect to an HTTPS website, here’s what happens:

- Client Hello: Your browser proposes encryption algorithms and sends a random number

- Server Hello: The server responds with its certificate (containing its public key), chooses encryption algorithms, and sends its own random number

- Key Exchange: Using algorithms like Diffie-Hellman or RSA, both parties derive a shared symmetric key without ever sending it across the network

- Finished: Both sides verify the handshake succeeded and begin encrypted communication

Copyrights © oracle docs

In TLS 1.2, this takes two round trips. TLS 1.3 optimizes it to one round trip, and for repeat connections, 0-RTT (zero round-trip time) allows sending encrypted data immediately using a pre-shared key.

Certificates and Trust:

Certificates are digital passports for websites. They contain:

- The server’s public key

- Identity information (domain name, organization)

- A digital signature from a Certificate Authority (CA)

Your browser trusts certificates signed by CAs in its certificate store (like Let’s Encrypt, DigiCert, or Cloudflare). This creates a chain of trust: you trust the CA, the CA vouches for the website, so you trust the website.

Key Exchange Algorithms:

-

RSA: The client encrypts the symmetric key with the server’s public key. Simple but lacks forward secrecy—if the private key is compromised later, past sessions can be decrypted.

-

Diffie-Hellman (DH): Both parties generate private numbers and use modular arithmetic to derive the same symmetric key without ever sending it. This provides forward secrecy because each session uses a unique key. Even if the server’s private key is compromised, past sessions remain secure.

TLS 1.3 mandates Diffie-Hellman, eliminating RSA’s forward secrecy problem.

Real-World Security:

The Heartbleed bug (2014) was a devastating vulnerability in OpenSSL that allowed attackers to read server memory, potentially exposing private keys. This highlighted the importance of forward secrecy—with RSA, attackers could decrypt all past recorded sessions. With Diffie-Hellman, past sessions remained secure.

Modern best practices include:

- Using TLS 1.3 (or at minimum TLS 1.2)

- Preferring Diffie-Hellman for forward secrecy

- Using short-lived certificates (weeks to months, not years)

- Enabling HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS) to force HTTPS

Performance Considerations:

TLS adds overhead:

- The handshake introduces latency (though TLS 1.3’s 1-RTT and 0-RTT help)

- Encryption/decryption requires CPU (though modern hardware has dedicated instructions)

- Certificates can be large, requiring multiple TCP segments

However, the security benefits far outweigh these costs, and optimizations like session resumption and 0-RTT minimize the impact.

3.4. HTTP/3 and QUIC (/kwɪk/): The UDP Revolution

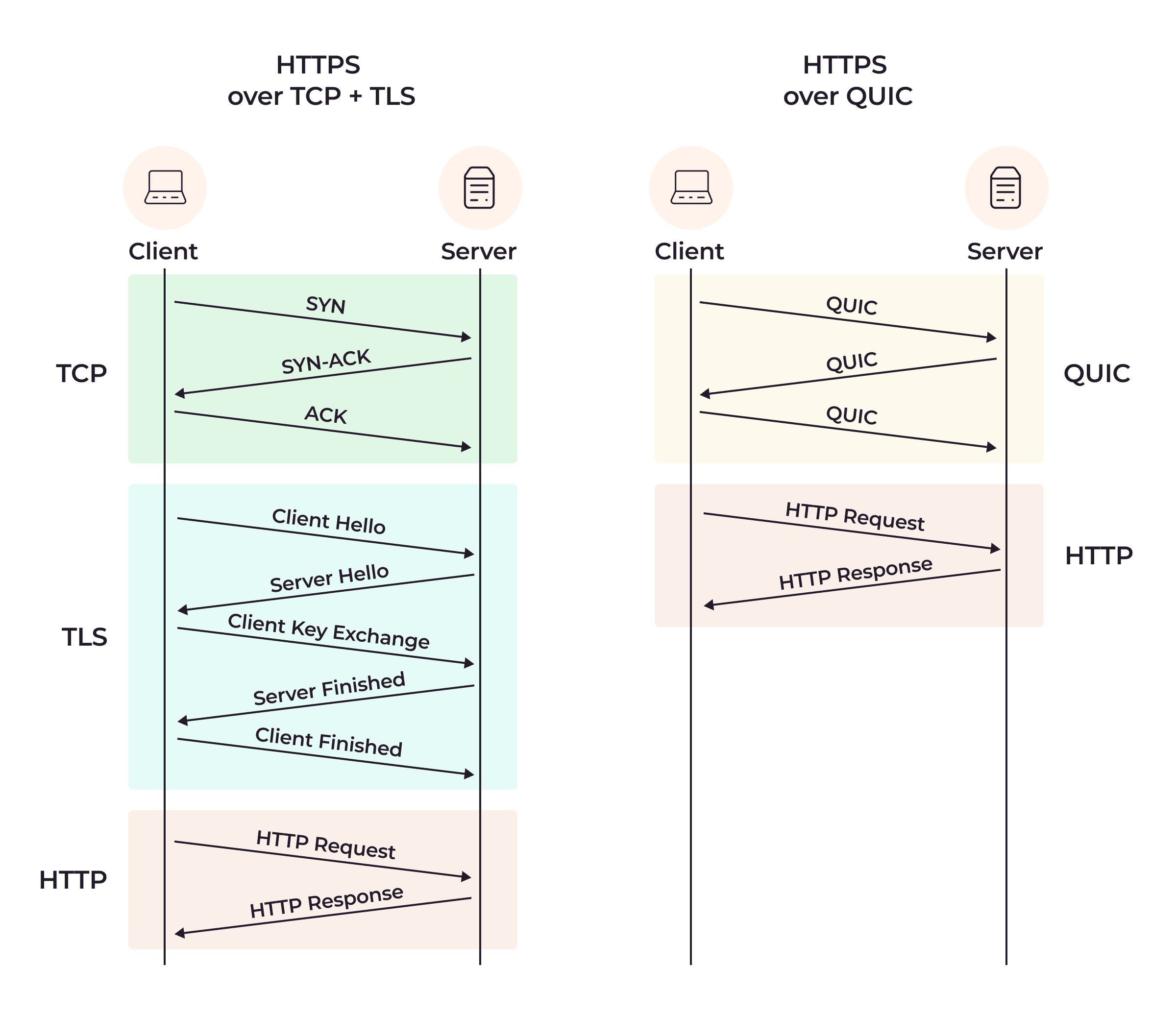

HTTP/3 represents a radical departure from its predecessors: it abandons TCP entirely in favor of QUIC (Quick UDP Internet Connections), a new protocol built on UDP. This might seem counterintuitive—didn’t we just learn that TCP is reliable and UDP is unreliable? The key insight is that QUIC implements reliability at the application layer, giving it flexibility TCP lacks.

The Problem HTTP/3 Solves:

HTTP/2’s Achilles’ heel is TCP head-of-line blocking. Even though HTTP/2 multiplexes streams at the application layer, TCP’s requirement for in-order delivery means a single lost packet stalls all streams. On lossy networks (like mobile connections), this can negate HTTP/2’s performance gains.

HTTP/3 solves this by using QUIC, which manages streams independently. A lost packet only affects its own stream, not others. This is a game-changer for performance on unreliable networks.

What is QUIC?

QUIC is a transport protocol that combines features of TCP, TLS, and HTTP/2 into a single layer. It runs over UDP but implements its own reliability, congestion control, and encryption. Think of it as “TCP done right for the modern internet.”

Copyrights © gcore

Key Features of HTTP/3:

-

Independent Stream Management: Each QUIC stream is independent. Lost packets only delay their own stream, eliminating head-of-line blocking entirely.

-

Faster Connection Setup: QUIC combines the transport handshake and TLS handshake into one step, reducing latency. For repeat connections, 0-RTT allows sending data immediately.

-

Connection Migration: QUIC uses connection IDs instead of the traditional four-tuple (source IP, source port, destination IP, destination port). This means connections survive network changes—like switching from Wi-Fi to cellular—without interruption. This is huge for mobile users.

-

Built-in Encryption: QUIC mandates TLS 1.3, making encryption a core feature rather than an add-on. This improves security and simplifies implementation.

-

Improved Congestion Control: QUIC’s congestion control is more sophisticated than TCP’s, adapting better to modern networks.

Copyrights © gcore

The Trade-offs:

HTTP/3 isn’t without challenges:

-

UDP Blocking: Some networks and firewalls block UDP traffic, preventing HTTP/3 from working. Implementations typically fall back to HTTP/2 or HTTP/1.1 in these cases.

-

Higher CPU Usage: QUIC handles tasks like stream management and encryption in user space rather than kernel space, requiring more CPU than TCP.

-

Complex Header Compression: HTTP/3 uses QPACK instead of HPACK, which is more complex to handle out-of-order delivery.

-

Security Concerns: Connection IDs are sent in plaintext, potentially allowing connection hijacking attacks. This is an active area of research.

-

Maturity: HTTP/3 is newer and less battle-tested than HTTP/2. Not all servers, clients, and intermediaries support it yet.

Performance in Practice:

HTTP/3 shines on lossy networks. On a perfect network with no packet loss, HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 perform similarly. But on mobile networks or congested connections where packet loss is common, HTTP/3’s independent stream management provides significant improvements.

Adoption:

Major players like Google, Facebook, and Cloudflare have adopted HTTP/3. Modern browsers (Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari) support it, and web servers like Nginx and Apache are adding support. The protocol is still evolving, but it’s clear that HTTP/3 represents the future of web communication.

When to Use HTTP/3:

HTTP/3 is ideal for:

- Mobile applications where network conditions vary

- Real-time applications sensitive to latency

- Global applications serving users on diverse networks

- Any scenario where connection migration is valuable

The Evolution Continues:

The progression from HTTP/1.1 to HTTP/3 shows how protocols evolve to meet changing needs:

- HTTP/1.1: Simple, reliable, but limited by one-request-per-connection

- HTTP/2: Multiplexing over TCP, but TCP head-of-line blocking remains

- HTTP/3: Multiplexing over QUIC/UDP, eliminating head-of-line blocking entirely

Each version builds on lessons learned from its predecessor. HTTP/1.1’s simplicity made it ubiquitous. HTTP/2’s multiplexing addressed the connection bottleneck. HTTP/3’s move to QUIC solves the last major performance issue.

As backend engineers, understanding these trade-offs helps us choose the right protocol for our applications. For simple APIs, HTTP/1.1 might suffice. For high-traffic websites, HTTP/2 is a solid choice. For mobile-first applications or real-time systems, HTTP/3’s benefits may be worth the added complexity.

The web continues to evolve, and HTTP/3 won’t be the final chapter. But for now, it represents the cutting edge of web protocol design, balancing performance, security, and reliability in ways previous versions couldn’t.

3.5. TLS/SSL: The Foundation of Secure Communication

While we’ve discussed HTTPS and TLS in the context of HTTP/3, it’s worth diving deeper into how TLS actually works under the hood. TLS (Transport Layer Security) is the backbone of internet security, and understanding its mechanics is crucial for any backend engineer building secure systems.

What is TLS?

TLS is a cryptographic protocol that provides three essential security features:

- Encryption: Scrambles data so only the intended recipient can read it

- Authentication: Verifies the server’s identity to prevent impersonation

- Integrity: Ensures data hasn’t been tampered with during transmission

Think of TLS as a digital lock that protects your data as it travels across the internet. When you see https:// in a URL, that’s HTTP running over TLS, ensuring your online banking, shopping, and private communications stay secure.

The Encryption Dance: Symmetric vs Asymmetric

TLS cleverly combines two types of encryption, each with different strengths:

Symmetric Encryption uses the same key for both encryption and decryption. It’s like a locked box where the same key locks and unlocks it. Algorithms like AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) and ChaCha20 are incredibly fast, making them perfect for encrypting large amounts of data like web pages or file transfers.

The challenge? Both parties need the same key, but how do you share it securely without someone intercepting it?

Asymmetric Encryption solves this problem using a public-private key pair. Think of it like a mailbox: anyone can drop a letter in (encrypt with the public key), but only the owner with the private key can open it and read the message. Algorithms like RSA and Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) enable secure key exchange without ever sending the private key across the network.

The trade-off? Asymmetric encryption is computationally expensive—all that exponential math takes time and CPU cycles, making it too slow for encrypting large amounts of data.

TLS’s Brilliant Solution:

TLS uses asymmetric encryption during the handshake to securely establish a shared symmetric key, then switches to symmetric encryption for the actual data transfer. You get the security of asymmetric encryption with the performance of symmetric encryption. It’s the best of both worlds.

The TLS Handshake: Establishing Trust

The TLS handshake is where the magic happens. It’s the process where client and server establish a secure connection before any sensitive data is exchanged. Let’s walk through it:

TLS 1.2 Handshake (Two Round Trips):

- Client Hello: Your browser sends a message proposing encryption algorithms (cipher suites) and a random number

- Server Hello: The server responds with its certificate (containing its public key), chooses encryption algorithms, and sends its own random number

- Key Exchange: Using algorithms like RSA or Diffie-Hellman, both parties derive a shared symmetric key

- Finished: Both sides verify the handshake succeeded and begin encrypted communication

This process takes two round trips—two complete back-and-forth exchanges between client and server. On high-latency connections, this delay is noticeable.

TLS 1.3 Handshake (One Round Trip):

TLS 1.3 streamlines this process dramatically:

- Client Hello: The client sends cipher suite proposals AND key exchange parameters in the first message

- Server Hello: The server responds with its certificate and key exchange parameters in one message

- Both parties immediately derive the symmetric key and start encrypted communication

By including key exchange parameters upfront, TLS 1.3 cuts the handshake to one round trip, significantly reducing latency. For repeat connections, TLS 1.3 even supports 0-RTT (Zero Round-Trip Time), where the client can send encrypted data immediately using a pre-shared key from a previous session.

Key Exchange Algorithms: RSA vs Diffie-Hellman

The choice of key exchange algorithm has significant security implications:

RSA Key Exchange:

In RSA, the client generates a random pre-master secret, encrypts it with the server’s public key, and sends it. The server decrypts it with its private key, and both derive the same symmetric key.

The problem? If the server’s private key is ever compromised—say, through a vulnerability like Heartbleed—an attacker who recorded past encrypted sessions can decrypt them all. RSA lacks forward secrecy.

Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange:

Diffie-Hellman takes a different approach. Both parties generate private numbers (let’s call them X and Y) and a shared public number (G). Using modular arithmetic, they compute:

- Client calculates: G^X mod N and sends it

- Server calculates: G^Y mod N and sends it

- Both can derive the same symmetric key: (G^X)^Y mod N = (G^Y)^X mod N

The beautiful part? The symmetric key is never transmitted across the network. Even if someone intercepts all the messages, they can’t derive the key without knowing X or Y.

More importantly, Diffie-Hellman provides forward secrecy. Each session uses unique, ephemeral keys that are discarded after use. Even if the server’s private key is compromised later, past sessions remain secure because the session keys no longer exist.

Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDH) is a more efficient variant using elliptic curve mathematics, providing the same security with smaller keys and less computation.

Certificates and the Chain of Trust

Certificates are digital passports for websites. They contain:

- The server’s public key

- Identity information (domain name, organization)

- A digital signature from a Certificate Authority (CA)

When you connect to a website, your browser verifies the certificate by checking:

- Is it signed by a trusted CA? (Your browser has a list of trusted root CAs)

- Is it valid? (Not expired, not revoked)

- Does the domain match? (The certificate’s common name matches the URL)

This creates a chain of trust: you trust the CA, the CA vouches for the website, so you trust the website. Root CAs like Let’s Encrypt, DigiCert, and Cloudflare are pre-installed in your browser or operating system’s certificate store.

The Heartbleed Lesson

The Heartbleed bug (2014) was a devastating vulnerability in OpenSSL that allowed attackers to read server memory, potentially exposing private keys, session keys, and user data. It highlighted two critical lessons:

-

Forward secrecy matters: With RSA, compromised private keys meant all past recorded sessions could be decrypted. With Diffie-Hellman, past sessions remained secure.

-

Certificate lifetime matters: Modern best practices use short-lived certificates (weeks to months, not years). Cloudflare, for example, uses certificates that expire in 2 weeks to 3 months. If a key is compromised, the window of vulnerability is limited.

TLS Versions: Evolution of Security

| Version | Status | Key Features | Security Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLS 1.0, 1.1 | Deprecated | Early standards | Vulnerable, not recommended |

| TLS 1.2 | Widely used | Two-roundtrip handshake, supports RSA | Lacks forward secrecy with RSA |

| TLS 1.3 | Modern standard | One-roundtrip handshake, mandates Diffie-Hellman | Enhanced security, forward secrecy, 0-RTT support |

TLS 1.3 represents a significant leap forward. It removes insecure cipher suites, mandates forward secrecy, and improves performance. As of 2024, over 95% of major browsers support TLS 1.3, and adoption is growing rapidly.

Performance Considerations

TLS adds overhead, but modern optimizations minimize the impact:

- Handshake Latency: TLS 1.3’s one-round-trip handshake reduces connection time by 50% compared to TLS 1.2

- 0-RTT: For repeat connections, 0-RTT eliminates handshake delays entirely, though it requires careful implementation to prevent replay attacks

- Session Resumption: Clients can reuse session parameters from previous connections, avoiding full handshakes

- Hardware Acceleration: Modern CPUs have dedicated instructions (AES-NI) for encryption, making symmetric encryption nearly free

- Certificate Compression: Reduces certificate size to minimize the number of TCP segments needed

The trade-off between security and performance has largely been solved. With TLS 1.3 and modern hardware, the overhead is minimal—typically adding only 10-20ms to connection establishment.

Practical Implementation

Implementing TLS in your applications involves several steps:

-

Obtain a Certificate: Use services like Let’s Encrypt for free, automated certificates, or purchase from commercial CAs for extended validation

-

Configure Your Server: Modern web servers like Nginx and Apache make TLS configuration straightforward:

server {

listen 443 ssl http2;

server_name example.com;

ssl_certificate /path/to/cert.pem;

ssl_certificate_key /path/to/private.key;

# Modern TLS configuration

ssl_protocols TLSv1.2 TLSv1.3;

ssl_prefer_server_ciphers on;

ssl_ciphers 'ECDHE-ECDSA-AES256-GCM-SHA384:ECDHE-RSA-AES256-GCM-SHA384';

}

- Enable HSTS: HTTP Strict Transport Security forces browsers to always use HTTPS:

add_header Strict-Transport-Security "max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains" always;

- Monitor and Renew: Automate certificate renewal (Let’s Encrypt certificates expire every 90 days) and monitor for security advisories

In Node.js, setting up an HTTPS server is straightforward:

const https = require('https');

const fs = require('fs');

const options = {

key: fs.readFileSync('private.key'),

cert: fs.readFileSync('cert.pem')

};

https.createServer(options, (req, res) => {

res.writeHead(200);

res.end('Secure connection established!');

}).listen(443);

Security Best Practices

Modern TLS deployment should follow these guidelines:

- Use TLS 1.3 (or at minimum TLS 1.2) and disable older versions

- Prefer Diffie-Hellman key exchange for forward secrecy

- Use short-lived certificates (90 days or less) to limit exposure

- Enable HSTS to prevent downgrade attacks

- Implement certificate pinning for high-security applications

- Monitor for vulnerabilities and apply patches promptly

- Use strong cipher suites and disable weak algorithms

The Future of TLS

TLS continues to evolve. Research focuses on:

- Post-quantum cryptography: Preparing for quantum computers that could break current encryption

- Encrypted Client Hello (ECH): Hiding the destination domain from network observers

- Improved 0-RTT security: Making zero-round-trip connections safer

- Certificate transparency: Public logs of all issued certificates to detect misissued certificates

Why This Matters

Understanding TLS isn’t just academic—it’s essential for building secure systems. Every time you:

- Design an API that handles sensitive data

- Configure a web server

- Debug connection issues

- Evaluate security requirements

- Choose between protocols

…you’re making decisions that depend on understanding how TLS works. The difference between RSA and Diffie-Hellman isn’t just theoretical—it determines whether your users’ past communications remain secure if your server is compromised.

TLS is the foundation of internet security. It protects everything from your online banking to your private messages. As backend engineers, we’re responsible for implementing it correctly, and that starts with understanding how it works under the hood.

Part III: Real-Time Communication

4. Real-Time Communication Technologies

Now that we’ve covered HTTP and its evolution, let’s explore technologies specifically designed for real-time communication. While HTTP works well for traditional request-response interactions, modern applications often need instant, bidirectional communication—think chat applications, live feeds, collaborative editing, or multiplayer games.

Real-time communication is about minimizing latency and enabling immediate data exchange. The technologies we’ll explore—WebSockets, Server-Sent Events, and polling—each take different approaches to this problem, with distinct trade-offs in complexity, performance, and use cases.

4.1. WebSockets: Full-Duplex Communication

WebSockets represent a fundamental shift from HTTP’s request-response model. They provide true bidirectional, full-duplex communication over a single TCP connection, allowing both client and server to send data at any time without waiting for the other party.

What Makes WebSockets Special:

Unlike HTTP, where the client always initiates requests and the server responds, WebSockets establish a persistent connection where either party can send messages independently. This is perfect for applications requiring instant updates in both directions—chat applications, live gaming, collaborative tools, and real-time dashboards.

The beauty of WebSockets is that they start as HTTP and then upgrade to a more efficient protocol. This clever design ensures compatibility with existing web infrastructure while providing the performance benefits of a persistent connection.

The WebSocket Handshake:

WebSockets begin with an HTTP connection that upgrades to a WebSocket connection through a handshake process. Here’s how it works:

- Client Request: The client sends an HTTP GET request with special headers indicating it wants to upgrade to WebSocket:

GET /chat HTTP/1.1

Host: servername

Upgrade: websocket

Connection: Upgrade

Sec-WebSocket-Key: dGhlIHNhbXBsZSBub25jZQ==

Sec-WebSocket-Protocol: chat

- Server Response: If the server supports WebSockets, it responds with HTTP 101 (Switching Protocols):

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocols

Upgrade: websocket

Connection: Upgrade

Sec-WebSocket-Accept: s3pPLMBiTxaQ9kYGzzhZRbK+xOo=

Sec-WebSocket-Protocol: chat

- Bidirectional Communication: After the handshake, the connection becomes a WebSocket connection. Both parties can now send messages in real-time without further HTTP overhead.

This handshake process is elegant—it uses HTTP to establish a secure connection before switching to a more efficient protocol. The Sec-WebSocket-Key and Sec-WebSocket-Accept headers provide security by preventing cross-protocol attacks.

Key Characteristics:

-

Bidirectional Communication: Both client and server can initiate data transfer at any time, enabling true push notifications from the server.

-

Built on HTTP: Uses HTTP for the initial handshake, ensuring security and compatibility with existing infrastructure.

-

Real-time Data Transfer: Supports instantaneous data exchange with minimal overhead once the connection is established.

-

Standard Ports: Uses ports 80 (ws://) and 443 (wss://), making it firewall-friendly and compatible with existing network infrastructure.

-

Stateful Connection: Unlike HTTP’s stateless nature, WebSockets maintain a persistent connection with session state.

-

Low Overhead: After the initial handshake, WebSocket frames have minimal overhead compared to HTTP headers, making them efficient for frequent small messages.

Practical Example: Building a Chat Application

Let’s look at a real implementation of a WebSocket-based chat application. This example demonstrates the push notification model, where the server instantly pushes messages to all connected clients without them needing to request updates.

Server-side implementation using Node.js and the ws library:

const WebSocket = require('ws');

const http = require('http');

const server = http.createServer();

const wss = new WebSocket.Server({ server });

let connections = [];

wss.on('connection', (ws) => {

connections.push(ws);

const remotePort = ws._socket.remotePort;

const joinMessage = `User ${remotePort} just connected`;

// Notify all clients about the new connection

connections.forEach((client) => {

if (client.readyState === WebSocket.OPEN) {

client.send(joinMessage);

}

});

// Handle incoming messages

ws.on('message', (message) => {

console.log(`User ${remotePort} says: ${message}`);

// Broadcast to all other clients

connections.forEach((client) => {

if (client.readyState === WebSocket.OPEN && client !== ws) {

client.send(`User ${remotePort} says: ${message}`);

}

});

});

// Handle disconnections

ws.on('close', () => {

connections = connections.filter((client) => client !== ws);

const leaveMessage = `User ${remotePort} disconnected`;

connections.forEach((client) => {

if (client.readyState === WebSocket.OPEN) {

client.send(leaveMessage);

}

});

});

});

server.listen(8080, () => {

console.log('WebSocket server running on port 8080');

});

Client-side implementation using the browser’s WebSocket API:

const ws = new WebSocket('ws://localhost:8080');

ws.onmessage = (event) => {

console.log('Received message:', event.data);

displayMessage(event.data);

};

function sendMessage(message) {

ws.send(message);

}

document.getElementById('sendButton').addEventListener('click', () => {

const message = document.getElementById('messageInput').value;

sendMessage(message);

});

This example shows how a few lines of code can create a functional real-time chat application. The server maintains an array of all connected clients, broadcasting messages to everyone except the sender. Messages appear instantly in all connected browsers, showcasing WebSockets’ speed.

The Trade-offs:

While WebSockets are powerful, they come with challenges:

-

Complexity in Management: Handling long-lived connections, especially with proxies and load balancers, can be tricky. Many proxies weren’t designed for persistent connections and may close idle WebSocket connections.

-

Stateful Nature: Makes scaling across multiple servers more difficult compared to stateless HTTP. You need strategies like sticky sessions or a shared message broker to ensure messages reach the right clients.

-

Connection Drops: Intermediaries like routers may close idle connections, requiring “ping-pong” messages (heartbeats) to keep them alive. This adds complexity to both client and server implementations.

-

Resource Intensive: Maintaining many open connections consumes significant server resources. Even advanced systems are limited to a few million connections per server.

-

Proxying Challenges: WebSocket proxying at Layer 7 is complex because proxies need to understand the WebSocket protocol. We’ll explore this more in the WebSocket Proxying section.

When to Use WebSockets:

WebSockets are ideal for:

- Chat applications and instant messaging

- Multiplayer games requiring low latency

- Collaborative editing tools (like Google Docs)

- Live dashboards and monitoring systems

- Any application requiring true bidirectional, real-time communication

However, WebSockets aren’t always the best choice. For simpler real-time needs where only the server pushes updates, alternatives like Server-Sent Events might be easier to implement.

4.2. Server-Sent Events: Unidirectional Streaming

Server-Sent Events (SSE) provide a simpler alternative to WebSockets when you only need unidirectional communication from server to client. SSE is perfect for scenarios like live feeds, notifications, or streaming responses—exactly what ChatGPT uses to stream its responses token by token.

What is SSE?

SSE is a one-way streaming protocol over HTTP where the server sends updates and the client receives them. Unlike WebSockets, which require a protocol upgrade and bidirectional communication, SSE uses standard HTTP with a special content type: text/event-stream.

The key insight is that SSE is simpler than WebSockets because it’s built directly on HTTP. There’s no protocol upgrade, no special handshake—just a regular HTTP request that the server keeps open to stream data.

How SSE Works:

The client makes a standard HTTP request, but instead of receiving a complete response and closing the connection, the server keeps the connection open and sends data as events:

// Client-side using EventSource API

const eventSource = new EventSource('/api/stream');

eventSource.onmessage = (event) => {

console.log('Received:', event.data);

};

eventSource.onerror = (error) => {

console.error('SSE error:', error);

};

The server responds with Content-Type: text/event-stream and sends data in a specific format:

data: First message

data: Second message

data: {"type": "update", "value": 42}

Each message is prefixed with data: and separated by blank lines. The browser’s EventSource API automatically handles parsing and reconnection if the connection drops.

ChatGPT’s SSE Implementation:

ChatGPT provides a fascinating real-world example of SSE in action. When you ask ChatGPT a question, the answer streams back token by token over an SSE connection. However, ChatGPT doesn’t use the standard EventSource API—instead, it uses a custom implementation with fetch() and stream readers for more control.

Here’s how ChatGPT’s streaming works:

async function streamChatResponse(message, conversationId, parentMessageId) {

const headers = {

'Content-Type': 'application/json',

'Authorization': `Bearer ${accessToken}`

};

const body = JSON.stringify({

message,

conversationId,

parentMessageId

});

const response = await fetch('/backend-api/conversation', {

method: 'POST',

headers,

body

});

const reader = response.body.getReader();

const decoder = new TextDecoder('utf-8');

let fullText = '';

while (true) {

const { done, value } = await reader.read();

if (done) break;

const chunk = decoder.decode(value);

fullText += chunk;

updateUI(chunk); // Update the chat window with new tokens

}

}

This approach gives ChatGPT fine-grained control over the stream, allowing it to handle errors, parse custom formats, and manage the UI updates precisely. The trade-off is that browser DevTools don’t show these as “EventStream” connections since they’re not using the standard API.

Key Characteristics:

-

HTTP-Based: Uses standard HTTP with

Content-Type: text/event-stream, making it simpler than WebSockets. -

Unidirectional: Only the server can send data; the client receives. For client-to-server communication, you still need regular HTTP requests.

-

Automatic Reconnection: The browser’s

EventSourceAPI automatically reconnects if the connection drops, with configurable retry intervals. -

HTTP/2 Multiplexing: Works beautifully with HTTP/2, allowing multiple SSE streams over a single TCP connection.

-

Text-Based: Events are text-based, making them human-readable and easy to debug.

SSE vs WebSockets:

When should you choose SSE over WebSockets?

-

Use SSE when: You only need server-to-client communication, want simpler implementation, or are already using HTTP/2 for multiplexing.

-

Use WebSockets when: You need bidirectional communication, want lower latency, or need to send binary data efficiently.

SSE’s simplicity is its strength. For many use cases—live feeds, notifications, streaming AI responses—SSE provides everything you need without WebSocket’s complexity.

4.3. Polling: The Traditional Approach

Before WebSockets and SSE, polling was the primary way to achieve “real-time” updates. While it’s less efficient than modern alternatives, polling is still relevant for legacy systems and situations where persistent connections aren’t feasible.

Short Polling:

Short polling is the simplest approach: the client repeatedly requests updates at regular intervals.

// Check for updates every 5 seconds

setInterval(async () => {

const response = await fetch('/api/updates');

const data = await response.json();

if (data.hasUpdates) {

updateUI(data);

}

}, 5000);

This is like constantly refreshing your email—wasteful and inefficient. Most requests return “no updates,” wasting bandwidth and server resources. The latency is also poor; updates can be delayed by up to the polling interval.

Long Polling:

Long polling is smarter. Instead of immediately responding with “no updates,” the server holds the request open until new data is available or a timeout occurs:

async function longPoll() {

try {

const response = await fetch('/api/updates?timeout=30');

const data = await response.json();

if (data.hasUpdates) {

updateUI(data);

}

// Immediately start the next long poll

longPoll();

} catch (error) {

// Wait a bit before retrying on error

setTimeout(longPoll, 5000);

}

}

longPoll();

The server holds the connection open until it has news, then responds and the client immediately makes another request. This reduces unnecessary requests and improves latency compared to short polling.

The Trade-offs:

Polling has significant drawbacks:

-

Inefficient: Short polling wastes bandwidth with constant requests. Long polling is better but still less efficient than persistent connections.

-

Latency: Short polling has inherent latency equal to the polling interval. Long polling is better but still involves request overhead.

-

Server Load: Each poll is a new HTTP request with full headers, creating overhead. With thousands of clients, this adds up quickly.

-

Scalability: Polling doesn’t scale well compared to WebSockets or SSE, especially for high-frequency updates.

When to Use Polling:

Despite its limitations, polling still has valid use cases:

- Legacy Systems: When you can’t modify the server to support WebSockets or SSE

- Firewall Restrictions: Some networks block WebSocket connections but allow HTTP

- Simple Requirements: For infrequent updates where efficiency isn’t critical

- Compatibility: When you need to support very old browsers

Comparison: Choosing the Right Approach

Here’s a practical comparison to help you choose:

| Method | Best For | Latency | Complexity | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WebSockets | Chat, gaming, bidirectional | Lowest | High | Good* |

| SSE | Notifications, feeds, streaming | Low | Medium | Excellent |

| Long Polling | Legacy compatibility | Medium | Low | Poor |

| Short Polling | Simple, infrequent updates | High | Lowest | Poor |

*WebSocket scalability requires careful architecture (sticky sessions, message brokers)

Real-World Considerations:

In practice, many applications use a combination of these technologies:

- WebSocket for the main real-time features (chat, live updates)

- SSE for server-initiated notifications and streaming responses

- Long polling as a fallback when WebSockets aren’t available

- Regular HTTP for traditional request-response interactions

The key is understanding your requirements. Do you need bidirectional communication? How many concurrent connections? What’s your latency tolerance? These questions guide your choice.

Modern frameworks often abstract these details, automatically choosing the best transport based on browser capabilities and network conditions. Socket.IO, for example, tries WebSockets first, then falls back to polling if needed.

The Evolution of Real-Time:

The progression from polling to WebSockets mirrors the evolution we saw with HTTP:

- Short Polling: Simple but inefficient, like HTTP/1.1’s one-request-per-connection

- Long Polling: Smarter but still wasteful, like HTTP/1.1 with Keep-Alive

- SSE: Efficient for unidirectional streaming, like HTTP/2’s server push

- WebSockets: True bidirectional real-time, optimized for modern needs

Each approach has its place. WebSockets and SSE represent the current state of the art, but polling remains relevant for specific scenarios. Understanding all these options makes you a better backend engineer, able to choose the right tool for each situation.

4.4. gRPC: Modern RPC Framework

While WebSockets and SSE excel at real-time browser communication, gRPC (Google Remote Procedure Call) takes a different approach, optimized for server-to-server communication in distributed systems. If you’re building microservices or need efficient communication between backend services, gRPC is a game-changer.

What is gRPC?

gRPC is a high-performance, open-source framework developed by Google that makes calling functions on remote servers feel like calling local functions. Instead of manually crafting HTTP requests and parsing responses, you define your service interface in a .proto file, and gRPC generates all the client and server code for you.

The brilliance of gRPC is that it combines the best of modern protocols: it runs on HTTP/2 for performance and uses Protocol Buffers for compact, efficient data serialization. This makes it significantly faster than traditional REST APIs using JSON over HTTP/1.1.

The Problem gRPC Solves:

Managing multiple client libraries for different communication protocols can feel like juggling too many balls at once. Each protocol—whether SOAP, REST, or GraphQL—comes with its own set of libraries that need constant updates and patches. In large enterprise systems where reliability is critical, this complexity becomes a real headache.

gRPC provides a unified solution: one framework, one client library, multiple programming languages. You define your service once, and gRPC generates idiomatic code for JavaScript, Python, Java, Go, C++, and many other languages. This dramatically simplifies maintenance and ensures consistency across your entire system.

Protocol Buffers: The Secret Sauce

Protocol Buffers (protobuf) are like a super-efficient version of JSON or XML. They let you define the structure of your data in a .proto file, which is then compiled into code for your chosen language. This ensures that data is small, fast to send, and easy to work with across different systems.

Here’s a simple example defining a to-do service:

syntax = "proto3";

package toDo;

message ToDoItem {

int32 id = 1;

string text = 2;

}

message NoParam {}

service ToDo {

rpc createToDo (ToDoItem) returns (ToDoItem);

rpc readToDos (NoParam) returns (ToDoItems);

}

message ToDoItems {

repeated ToDoItem items = 1;

}

This .proto file defines a ToDo service with two methods: createToDo to add a new to-do item and readToDos to retrieve all items. The repeated keyword indicates an array of items. Once you compile this, gRPC generates all the boilerplate code for both client and server.

Key Characteristics:

-

HTTP/2 Based: Leverages HTTP/2’s](#http-2) advanced features like multiplexing (handling multiple requests simultaneously), header compression, and streaming. This means you can send multiple gRPC calls over a single TCP connection without blocking.

-

Binary Protocol: Uses Protocol Buffers’ compact binary format instead of text-based JSON. This makes messages smaller and faster to parse, though less human-readable.

-

Strongly Typed: The schema is defined upfront, providing compile-time type checking and preventing many runtime errors. This is a double-edged sword—it adds safety but reduces flexibility.

-

Language Agnostic: Supports many programming languages, making it easy to connect services written in different languages. Your Python service can seamlessly call your Go service.

-

Single Client Library: Provides one library managed by Google and the community, reducing the need to juggle multiple libraries and ensuring consistent behavior across languages.

Communication Patterns:

gRPC supports four communication patterns, making it incredibly versatile:

-

Request-Response (Unary): The classic pattern—client sends a request, server sends back a response. This is like a traditional REST API call but faster.

-

Server Streaming: The client sends one request, and the server responds with a stream of messages. Perfect for scenarios like downloading a large file in chunks or subscribing to real-time updates.

-

Client Streaming: The client sends a stream of messages, and the server responds with a single message. Great for uploads or aggregating data from the client.

-

Bidirectional Streaming: Both client and server send streams simultaneously. This is similar to WebSockets but optimized for server-to-server communication. Ideal for real-time applications like chat or live monitoring.

This flexibility is one of gRPC’s biggest strengths. You can use simple request-response for most operations, then switch to streaming for specific use cases without changing your infrastructure.

Practical Example: Building a To-Do Service

Let’s see gRPC in action with a Node.js implementation. After defining the .proto file above, here’s the server implementation:

const grpc = require('grpc');

const protoLoader = require('@grpc/proto-loader');

const packageDefinition = protoLoader.loadSync('todo.proto', {});

const grpcObject = grpc.loadPackageDefinition(packageDefinition);

const toDoPackage = grpcObject.toDo;

const server = new grpc.Server();

let todos = [];

server.addService(toDoPackage.ToDo.service, {

createToDo: (call, callback) => {

const newTodo = { id: todos.length + 1, text: call.request.text };

todos.push(newTodo);

callback(null, newTodo);

},

readToDos: (call, callback) => {

callback(null, { items: todos });

}

});

server.bind('0.0.0.0:40000', grpc.ServerCredentials.createInsecure());

server.start();

console.log('gRPC server running on port 40000');

The server stores to-do items in an array and handles requests to create and read to-dos. Notice how clean this is—no manual HTTP parsing, no JSON serialization. gRPC handles all of that.

The client is equally straightforward:

const client = new toDoPackage.ToDo('localhost:40000', grpc.credentials.createInsecure());

client.createToDo({ id: -1, text: 'Do laundry' }, (error, response) => {

if (!error) console.log('Created ToDo:', JSON.stringify(response));

});

client.readToDos({}, (error, response) => {

if (!error) console.log('ToDos:', JSON.stringify(response.items));

});

This client creates a to-do item and retrieves the list of all to-dos. The API feels like calling local functions, even though it’s making network requests under the hood.

Streaming in Action:

To demonstrate gRPC’s streaming capabilities, we can modify readToDos to stream each to-do item individually:

Server-side:

readToDosStream: (call) => {

todos.forEach(todo => call.write(todo));

call.end();

}

Client-side:

const call = client.readToDosStream({});

call.on('data', (item) => console.log('Received item:', JSON.stringify(item)));

call.on('end', () => console.log('Server done'));

This demonstrates how gRPC can stream data, which is useful for applications needing real-time updates or large data transfers. The streaming API is event-driven, similar to Node.js streams, making it familiar to JavaScript developers.

gRPC vs REST: When to Use Each

The comparison between gRPC and REST is one of the most common questions in backend engineering. Here’s how they stack up:

gRPC Advantages:

-

Performance: Binary Protocol Buffers are more compact than JSON, and HTTP/2 multiplexing reduces latency. In benchmarks, gRPC is often 5-10x faster than REST for equivalent operations.

-

Streaming: Native support for bidirectional streaming, which is cumbersome to implement with REST.

-

Type Safety: Strongly typed schemas catch errors at compile time, reducing runtime bugs.

-

Code Generation: Automatic client and server code generation saves development time and ensures consistency.

-

Cancelable Requests: You can cancel in-flight requests, which is tricky with traditional HTTP.

REST Advantages:

-

Simplicity: REST is simpler to understand and debug. You can test REST APIs with curl or a browser; gRPC requires specialized tools.

-

Browser Support: REST works natively in browsers; gRPC requires a proxy (gRPC-Web) to work in browsers, adding complexity.

-

Flexibility: REST with JSON is schema-less, allowing rapid iteration without recompiling. gRPC requires updating the

.protofile and regenerating code. -

Ecosystem: REST has a mature ecosystem with extensive tooling, documentation, and developer familiarity.

-

Human-Readable: JSON is easy to read and debug; Protocol Buffers are binary and require tools to inspect.

When to Use gRPC:

- Microservices: When you have many services communicating frequently, gRPC’s performance and type safety shine.

- Real-Time Systems: Streaming support makes gRPC ideal for real-time data pipelines or monitoring systems.

- Polyglot Environments: When services are written in different languages, gRPC’s cross-language support is invaluable.

- Performance-Critical Applications: When every millisecond counts, gRPC’s efficiency makes a difference.

When to Use REST:

- Public APIs: REST is more accessible to external developers and works in browsers without additional setup.

- Simple CRUD Operations: For straightforward create-read-update-delete operations, REST’s simplicity is often sufficient.

- Rapid Prototyping: When you need to iterate quickly without worrying about schemas.

- Legacy Integration: When integrating with systems that only support HTTP/1.1 or JSON.

The Trade-offs:

gRPC isn’t perfect for every situation. Here are the challenges you’ll face:

-

Schema Dependency: You must define a schema upfront, which can slow down development compared to schema-less options like REST with JSON. Every change requires updating the

.protofile and regenerating code. -

Thick Client: The client libraries can have bugs or security issues that need monitoring. You’re dependent on Google and the community for updates.

-

Complex proxies: Setting up proxies or load balancers for gRPC can be tricky. Many traditional HTTP proxies don’t understand gRPC’s streaming semantics, requiring specialized configuration.

-

No Native Error Handling: gRPC provides status codes, but developers must build their own error-handling logic. There’s no standardized error format like REST’s HTTP status codes.

-

No Browser Support: Browsers don’t natively support gRPC, requiring workarounds like gRPC-Web proxies. This adds complexity and latency for web applications.

-

Connection Issues: Long-running connections may face timeouts, and TCP connections can drop, needing reconnection logic. This is similar to WebSocket challenges.

Real-World Example: Spotify’s Switch to gRPC

Spotify provides a fascinating case study. They initially built their own custom protocol called Hermes for internal service communication. However, they eventually switched to gRPC due to its widespread adoption and strong community support.

The lesson? Building custom protocols is expensive. Unless you have very specific requirements that existing protocols can’t meet, adopting a well-established protocol like gRPC saves time and leverages community-driven improvements. Spotify’s experience shows the value of choosing battle-tested solutions over reinventing the wheel.

gRPC in the Modern Stack:

gRPC has become a cornerstone of modern microservices architectures. Companies like Google, Netflix, Square, and Cisco use it extensively for internal service communication. It’s particularly popular in cloud-native environments where services are containerized and orchestrated with Kubernetes.

The typical pattern is to use gRPC for internal service-to-service communication (where performance and type safety matter) and REST for public-facing APIs (where simplicity and browser compatibility matter). This hybrid approach gets the best of both worlds.

Comparison with Other Protocols:

To put gRPC in context, here’s how it compares to other protocols we’ve discussed:

| Protocol | Best For | Latency | Complexity | Browser Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| REST | Public APIs, simple CRUD | Medium | Low | Native |

| gRPC | Microservices, streaming | Low | Medium | Requires proxy |

| WebSockets | Browser real-time | Lowest | High | Native |

| SSE | Server push to browsers | Low | Low | Native |

gRPC occupies a unique niche: it’s optimized for server-to-server communication where performance and type safety are critical. It’s not trying to replace REST for public APIs or WebSockets for browser communication—it’s solving a different problem.

Getting Started with gRPC:

If you’re interested in trying gRPC, here’s the typical workflow:

-

Define Your Service: Write a

.protofile describing your service interface and data structures. -

Generate Code: Use the Protocol Buffers compiler (

protoc) to generate client and server code for your language. -

Implement the Server: Write the business logic for your service methods.

-

Create Clients: Use the generated client code to call your service from other applications.

-

Deploy and Monitor: Deploy your gRPC services and monitor their performance and health.

The official documentation at grpc.io provides excellent tutorials and examples for getting started in various languages.

The Future of gRPC:

gRPC continues to evolve. Recent developments include:

- gRPC-Web: Improved browser support through a JavaScript library and proxy

- gRPC-Gateway: Automatic REST API generation from gRPC services

- Better Observability: Integration with tracing and monitoring tools like OpenTelemetry

- Performance Improvements: Ongoing optimizations to reduce latency and resource usage

As microservices architectures become more prevalent, gRPC’s role in backend engineering will only grow. Understanding how it works and when to use it is becoming an essential skill for backend engineers.

Why This Matters:

gRPC represents a shift in how we think about service communication. Instead of treating services as HTTP endpoints that return JSON, gRPC treats them as remote objects with methods you can call. This abstraction makes distributed systems feel more like monolithic applications, reducing the cognitive overhead of network communication.

The choice between gRPC and REST isn’t about one being better than the other—it’s about choosing the right tool for the job. For internal microservices where performance and type safety matter, gRPC is often the better choice. For public APIs where simplicity and accessibility matter, REST remains king. Understanding both makes you a more versatile backend engineer.

4.5. WebRTC: Peer-to-Peer Communication

While WebSockets, SSE, and gRPC all involve communication through servers, WebRTC (Web Real-Time Communication) takes a radically different approach: it enables browsers and mobile apps to communicate directly with each other, peer-to-peer. This is the technology powering video calls in Google Meet, voice chat in Discord, and real-time collaboration tools—all without requiring users to install additional software.

What is WebRTC?

WebRTC is a free, open-source project that provides browsers and mobile applications with real-time communication capabilities through simple APIs. The key insight is that WebRTC creates direct connections between users, cutting out the middleman. Instead of your video call going through a server (which adds latency and costs), WebRTC connects you directly to the other person’s device.

Think of it like this: traditional communication is like sending a letter through the post office, while WebRTC is like walking next door and talking to your neighbor directly. The direct path is faster and more efficient.

The Challenge: NAT and Firewalls

Here’s where things get interesting. Most of us sit behind routers at home or work, and these routers use NAT (Network Address Translation) to manage multiple devices sharing one public IP address. NAT is like a gatekeeper that translates your device’s private address (like 192.168.1.5) to a public one that the internet can see.

The problem? NAT makes it tricky for two devices to find and connect to each other directly. Your device doesn’t know its public IP address, and even if it did, the router might block incoming connections. WebRTC has to work around these obstacles to establish peer-to-peer connections.

NAT Types and Their Impact:

Not all NAT implementations are created equal. The lecture explained different NAT types:

-

Full Cone NAT: The easiest to work with. Once your device sends data out through a port, anyone can send data back to that port. This is like leaving your front door unlocked—convenient for WebRTC but less secure.

-

Restricted Cone NAT: More selective. Only devices you’ve communicated with can send data back. This is like having a guest list at your door.

-

Port Restricted Cone NAT: Even more restrictive. Not only must you have communicated with the device, but it must use the same port. This adds another layer of security but makes connections harder.

-

Symmetric NAT: The trickiest for WebRTC. Your router assigns different public ports for different destinations, making it nearly impossible for peers to predict how to reach you. This is like changing your address every time you send a letter—secure but problematic for direct connections.

STUN: Discovering Your Public Address

STUN (Session Traversal Utilities for NAT) servers help your device figure out its public IP address and port. It’s like asking a friend, “Hey, what’s my address from the outside world?”

Here’s how it works: